Sia’s “Elastic Heart” Video & the Romantic Ideal

A little while back a friend of mine suggested I watch Sia’s “Elastic Heart” video starring Shia LaBeouf and Maddie Ziegler and wanted me to give my opinion of this beautiful but provocative video. This suggestion and request led to me going interpretively nuts on it, as well as a considerable amount of face-palming whilst reading through some of the comments and reactions to the video by those considering it some form of pedophilia. This controversy eventually resulted in a desire to write this article.

It is my understanding that the video has very little to do with pedophilia. This interpretation comes, as one YouTube commentator aptly put it, from the projection of these experiences onto the video. It is true that on a certain level the video can be viewed in this manner, but I feel that this is a far too simplistic and misguided interpretation. What the video is portraying is instead much deeper and is, as I will argue below, closely related to the Romantic ideal of childlike innocence and a desire, struggle and eventual inability to completely return to this state.

Can You Hear Me?

The Importance of Voice in Identity and the Recognition of the Other.

In this article I will argue for the importance of Voice in our understanding of human identity and argue that the recognition of the Other is not dependent on vision alone but is supported by at least two of the other senses; touch and hearing.

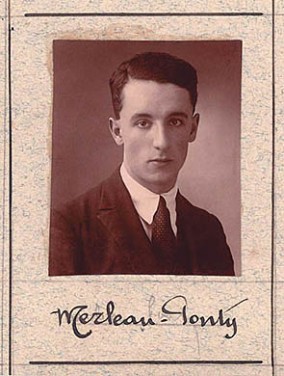

A child’s vision takes time to develop, a new born can only distinguish forms and object a couple of inches away, yet their hearing and sense of touch are often more, or even fully, developed at birth. Indeed a baby, before being able to recognize the Other visually and before they are aware of their bodily limits and image, Lacan’s ‘mirror stage’, they, through touch, are able to recognize the difference between touching and being touched, in other words, the physical limitation of their body. Or as Merleau-Ponty (1962) argues on the importance of the body; ‘the body catches itself from the outside engaged in a cognitive process […] and initiates ‘a kind of reflection’ which is sufficient to distinguish it from objects.’(107).

Perfomativity in the Post-Human

The reappropriation of performativity in Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and Synecdoche New York.

In Bodies That Matter Judith Butler argues for a different understanding of gender and sexuality than was previously accepted. In this text Butler coins the term performativity in relation to gender roles and gender identity. Butler argues that none of us are born with a gender but that what we perceive as gender roles are social constructs. This idea of gender roles, or “sex” as Butler labels it, as a social construct does however come with a problem as ‘this relation between culture and nature implies a culture or an agency of the social which acts upon a nature, which is itself presupposed as a passive surface, outside the social and yet its necessary counterpart’. The problem that has raised the issue of performativity for Butler is the idea that ‘bodies never quite comply with the norms by which their materialization is impelled’ (2)

Butler further argues that, once the normative ideal has been accepted, we are compelled to then act upon this ideal of gender roles and relate our own gender identity with this and perform accordingly, to act as is expected of us by both the Other and the Self. Butler continues by arguing that this act is exactly that, an act, or a performance. This performance is however a complicated idea as this performance of gender roles is different from that of actors on a stage. She thus labeled it performativity which she defines ‘not as a singular or deliberate “act,” but, rather, as the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects that it names’ and produces ‘the phenomena that it regulates and constraints.’(2) Butler finally argues that the concept of performativity results in a radical ‘rethinking of the process by which a bodily norm is assumed, appropriated, taken on as not, strictly speaking, undergone by a subject, but rather that the subject, the speaking “I,” is formed by virtue of having gone through such a process of assuming a sex.’(3)

In this article I will look at three contemporary texts which, as I will argue, have taken the construct of performativity beyond the limits of gender roles and gender identity. I will argue that the 2006 novel Remainder by Tom McCarthy, Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 novel Never Let Me Go and the 2008 movie Synecdoche, New York have taken Butler’s concept out of issues of gender and reapporpriated them for the post-human concept of identity and the disassociation of the self. I will argue that the forming of the subject through the assuming of a sex by performativity and normative ideals is not only limited to gender roles but is, in post-human society, further developed to envelop all of identity, the self, and our understanding of the human.

H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine and ADHD’s Implications For Education

A little while ago I decided to reread father of science fiction H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine after obtaining an absolutely gorgeous illustrated edition published by the Folio Society. Whilst reading through this short story I came across a particular section which sparked a new idea and again suggested to me the brilliance of Wells’ writing.

Part of The Time Machine’s charm lies in the speculations and theories with which the protagonist. the time traveller, tries to understand the strange sights, experiences, and societies of this future earth. The passage i was referring to earlier is one of the Time Traveller’s attempts to address the evolution of these new human-like beings that appear to populate earth at that future time, the Eloi;

“Humanity had been strong, energetic, and intelligent, and had used all its abundant vitality to alter the conditions under which it had lived. […] Under the new conditions of perfect comfort and security, that restless energy, that with us is strength, would become weakness. Even in our own time certain tendencies and desires, once necessary to survival, are a constant source of failure” (38-39)

Depicting War; Pavese & Rossellini on Italy’s WWII

Nothing feeds forgetfulness better than war. However, every age remains in the memory of those who lived through it and in the memory of those generations that follow. It is through the media of their time that these later generations are reminded of the events that took place before theirs.

However, every generation has its own internal logic, its own structure of feeling. Therefore, to truly understand what happened during a certain time period, one must look at the works contemporary of that time. It is through the films and literature of that place and period that we are reminded of stories and perspective of a war that would otherwise have been forgotten.

Two classic works that deal with Italy during World War II, a story often ignored in modern works today, are the neo-realist film Paisa by Roberto Rossellini and the novel La Luna e i Falo or The Moon and the Bonfires by Cesare Pavese. Both works, though different in their chosen portrayal of the war, both deal with the importance of time passing and memory. With this essay I shall look at both these works and show the different ways in which both of them show the importance of time passing and memory in the representation of war.

Only Revolutions- Mark z. Danielewski’s Answer to the Ebook Debate

Anyone familiar with the name Danielewski is familiar with challenging books. Of those readers most will have read, or at the very least attempted to read, Danielewski’s masterful and best-selling debut “novel” House of Leaves. His second novel Only Revolutions is just as experimental in its use of the concept “the book” as his first. Anyone who has attempted to read Danielewski’s House of Leaves has experienced a sense of dread and excitement whilst leaving through its pages for the first time and most will have wondered how to actually go about reading the text with all its interwoven story archs. A similar literary challenge is presented to the reader with Only Revolutions.

The Zombie Narrative & Political Discourse

Anyone even slightly interested in contemporary (pop) culture could not have helped but notice a steady increase and popularity of the zombie narrative in recent years after a significant period of having been marginalized to the fringes of contemporary culture and pulp fiction. A narrative that has often been dismissed as nothing more than brainless (pun intended) entertainment.

In recent years the zombie narrative van be said to be resurging and becoming more and more popular and mainstream. Movies such as “28 days/ Weeks Later”, “Shaun of the Dead”, “Resident Evil”, “Planet Terror”, and hosts of others have been coming out in increasing numbers and gaining more and more popularity. And I am not even mentioning the enormous popularity of “The Walking Dead” both graphic novel and tv series. With this rediscovery of the genre also comes the question as to why these zombies have been rearing their undead heads again in popular culture after so many years of absence.

Banksy and the Global

As Kwame Anthony Appiah neatly describes in his book Cosmopolitanism, the way human beings interact and are exposed to each other has changed considerably . We used to spend most our lives within a single tribe, in which all of the faces we would meet during the day were those we had met all other days of our lives. Nowadays however, the massive increase of global population and the rise of large populated cities, populations which until relatively recent were unimaginable, force us to be confronted with a large number of faces, of which only a small part of a percentage makes up those we know. As Appiah argues; ‘once we started to build these larger societies, most people knew little about the ways of other tribes, and could affect just a few local lives.’ (10) However, as Ulrich Beck argues, the advent of cosmopolitanism and cosmopolitanization gave rise to a host of new problems and questions. Indeed one of these is the notion that ‘ideas of global concerns are becoming part of the everyday local experiences and the “moral life-worlds” of the people’(17) Beck further asks that with the rise of

‘can the reasons which a society gives for the exclusion of strangers be questioned by members of this society and strangers alike? […] For example, may ‘foreigners’ participate in the process of discussion, definition and decision-making when it comes to the issue of civil rights?’(20)

In this essay I will argue that graffiti stencil art is a way of addressing and overcoming these and other issues put forth by globalization theorists. I will do this by focusing primarily on the Palestine wall pieces done by British graffiti artists Banksy.

Paul Auster’s – Winter Journal

Published thirty years after the publication of his debut novel The Invention of Solitude Paul Auster’s latest novel Winter Journal can (and has been) read as a continuation or rather a sequel of this first book. There are however striking differences between the two novel, something to be expected with a thirty year gap in between. More about this in a later post. For now I will first however address this novel on its own (and plentiful) merits.

Auster’s Winter Journal is, in its essence, a highly personal working through of questions that arise from getting older, of discovering that life’s good, the bad, and the traumatic experiences are ultimately finite and death comes for all at one point or another.

This reworking of the biographical novel opens several days before Auster’s 64th birthday as he sits himself in front of his desk and begins the mull over his life and the text itself is a detailed account of it. This in itself is very nicely done and is certainly interesting for anyone trying to discover some of the secrets of this grandmaster of the postmodern novel. Indeed I suspect many prospective writers and students of literature will find this novel quite alluring as it gives a first-person account of the life of a writer. Yet any trying to attain an insight into Auster’s means of writing, of discovering how he writes what he writes will sadly be left disappointed.

Winter Journal, however, does something far more interesting than giving a peak into the inner workings of a literary mind. With this novel Auster is trying to over come that which many of his protagonists of his novels (The New York Trilogy, Oracle Night, The Country of Last Things etc etc) experience or suffer through, a loss of self and identity and to me Auster is attempting to cope with or even overcome this loss in much the same way that his protagonists do. By writing. In some way this reading is highly reminiscent of Auster’s novel Man in Dark in which fiction and reality are intertwined (as with most Auster novels) and in which the “real” protagonist, a storyteller meets his fictional creation. In a sense this is similar to what happens in Winter Journal, Auster’s fiction has become real. Auster himself, in this autobiography is experiencing that which he has written about on so many occasions and is working through it in the same way his fictional characters have, by writing.

By the act of writing Winter Journal Auster has turned the page and ink receiving his thoughts into a symbolic other (in a Lacan and Butler sense) upon which to construct and reconstruct his own identity, something to reassess his sense of self upon. Winter Journal should thus be read as a diary of a man, late in life, trying to figure out who he was and who he is. Through this text Auster is taking stock of his own life, trying to find himself, or at the very least trying to make sense of who he is now that old age is distancing himself from his body, a body that is failing him more often, a body which through all its scars and marks should tell him who he is.

In conclusion then, this new novel by Paul Auster is something completely different from what one would expect to read in an autobiography. It is not a tale of a man relating his life story, it is the wanderings of a mind trying to come to terms with himself. In this it is a powerful and unique read. It is the search for the self that comes with old age, a search for understanding, and in doing this it is a novel which does what many texts try to do yet only the good ones achieve, one of the main purposes of good literary work; it teaches how to live, how to experience and how to cope with growing older, when our bodies can no longer do all the things we once could.

(Post)Modern “I” and Other in Auster, Nijhoff & Stein

Representing Genocide in the Graphic Novel

One of the problem that many survivors of violence, horror and genocide, in particular those that survived the Holocaust, experienced, was their inability of using language to clearly convey their lived experiences. Many of those who tried, i.e. Eli Wiesel, Primo Levi, Art Spiegelman, Joe Sacco etc, came to the realization that there was a gap between the linguistic signs and the actual experience; there was a gap between the language they used to represent the violence and their lived experience of violence.

Here I will argue that the comic book medium, with particular focus on Art Spiegelman’s Complete Maus (1996) and Joe Sacco’s Safe Area Gorazde (2007), might in fact offer the authors, both dealing with violence on such a grand scale as witnessed by those who lived through genocide, unique possibilities and capabilities. I will argue that the very reason many look at the comic book medium as the ‘dumber brother of literature’, it being, to many, a book with pictures, might in fact offer us ways of filling in the gap between representations of violence and the actual lived through experience more than any other medium has been able to do. In this essay I will first look at the problems both authors are faced with. This essay will then look at the ways through which both authors have dealt with this problem in their own unique medium specific ways.

Being Decentered in Sandman

In his article ‘Being’ Decentered in Sandman Rodney Sharkey argues that Neil Gaiman in his series destabilizes phallocentric and patriarchal discourse. According to Sharkey he does this throughout the series in different ways.

One of the elements through which Gaiman does this is through his de-centering of the central core required for the interpretation of discourse. Throughout his series Gaiman keeps shifting the center that Jacques Derrida argues is central to language and required for interpretation. Sharkey argues that through the constant switching between the real world and the dream world Gaiman keeps de-centralizing our interpretive framework. In The Sandman series it is impossible to define which plain of existence is the actual real, or the centre. Both the ‘real’ world and the dream world influence each other through numerous means which makes it impossible to define a hierarchy between these two elements.

This destabilizing of the binary nature of the real and the dream Gaiman removes one of the differences upon which the interpretation of phallocentric and patriarchal discourse, according to Derrida, is dependant. Or as Sharkey puts it “our received barriers regarding modes of representation […] are […] transgressed.”(Sharkey, 2010: 12) This removal of the differences, upon which discourse is dependant, of the real and the dream is only one feature through which Neil Gaiman does this.

Another way through which Gaiman has de-stabilized the heterocosm in The Sandman is through his representation of a god and his incorporation of numerous religions all of which appear to have a fluid identity. Within the series there is mention of a creator deity – the shaper- but is never referred to as God in the Christian/ monotheistic sense of the word. With the series the Shaper is an indifferent deity which creates but does not influence when looking at those that could be labeled as the shaper of destiny or the influencers of the world one quickly arrives at the entities called ‘the endless’.

These six (or actually seven) entities are however better defined as concepts. But even these concepts are not stable or centered but fluid and changing, plagued by the duality of their nature. They are both independent and dependent on each other for their existence, one requires the others existence. Even the main protagonist of the series, Dream, is plagued by the duality of his nature and the absence of a binary divide of his identity and destiny. In fact, one of the Endless actually stopped fulfilling his role and disappears.

Within The Sandman series it would seem then that the reader, but also every entity in the series is stuck within the first of the three Lacanian orders ‘the real’ as nothing is separate from the other and everything is part of everything else. The binary divide upon which language is structured appears to have been removed in favor of fluidity in identity and it is impossible to create a stabilized hierarchy within the text.

On ‘Iconicity’ in Scott McCloud’s – Understanding Comics

In Understanding Comics Scott McCloud argues that one of the fundamental characteristics of comics is their use of the icon. He defines this as “any image used to represent a person, place, thing or idea.” (27) He continues this argument by claiming it is the universality of the simplistic icon in comics that attributes to its large-scale appeal, and that through emphasizing simplicity in their art, artists move away from reality and move into the realm of concepts. He supports this argument by claiming we “sustain a constant awareness of […] [our] own face” (36) which according to McCloud closely resembles that of a simplistic rendering of ourselves. Or, in other words, the way we picture ourselves in our mind’s eye is incomplete, simplistic and void of any details. McCloud argues that the more simplistic or abstract a rendering is, the more easily we can identify with it. Or as he put it; “it is a void which enables us to travel in another realm”. Simplistically put, McCloud argues that the more realistic an image becomes the more ‘other’ it becomes and the harder it will be for us to empathize with it.

This idea of ‘other’ resembles Lacanian concepts of ‘other’. According to Lacan there are two types of ‘Other’; the little other and the ‘big Other’. The little other, according to Lacan, is not really other but is the projection of the Ego (Evans 30) whereas the ‘big Other’ designates a radical alterity. An important element for the little other, and necessary to support McCloud’s theory, is Lacan’s concept of the Counterpart and Transitivism. According to Lacan the counterpart comes from the realization that someone is similar. The counterpart is also “interchangeable with the image of the subject’s own body.”(Evans, 30). I believe that the universality of the icon, and thus of comics, is not so much due to its abstractness but by its lack of differences which might designate it as a ‘big other’ and thus the emphasis on similarities. And because of the recognition as the icon to be similar, and through transitivism the more iconic a rendering becomes, the less it focuses on reality, detail and differences, it moves more and more away from being a ‘big other’ and more towards that of ‘little other’

If we, however, follow this train of thought in accordance to McCloud’s theory, there is one obstacle in the way of our ability to transcend the ‘big Other’, and that is his claim on the iconicity of letters and words. According to McCloud the most iconic renderings in society are words as they reside completely in the realm of concepts. It could therefore be argued that the medium that comes closest to removing the barrier of the ‘big other’ is that which utilizes the most conceptual renderings, i.e. non-described characters in text. This however, then, undermines the necessity of pictorial representations as used in comics as they will only hinder this transitivism and they will always remain more rooted in the ‘big Other’ and thus rendering Mccloud argument for comics universal appeal over other media, through pictorial iconicity, void and unnecessary

The Death of Great (Dutch) Literature (My Intial Ramblings)

It has been my observation that the death of good, and especially great, literature in Western Europe, and specifically Dutch literature, is caused by the long absence of a shared social tragedy as well as the complete and utter disappearance of the grand narratives.

It has long been my believe that great literature can only be written during or after moments of tragedy, depression, social injustice or times of social struggle. In The Netherlands, which has never really been renowned as a great literary nation, the last two large scale social tragedies happened more than half a century ago – World War II and the great flood of 1953- have faded from the shared public conscious and now reside in the unconscious of the few.

Even the large social struggle of the 1960s seemed to have passed by The Netherlands at the fringes. Although the social plights where there, and I am not arguing their importance, they not of the same magnitude and on such great injustices as they where in such countries as America, the UK, Japan or Latin America.

This lack of a shared conscious disbelief on their or other’s places in society or the injustices done to them, which in real life is a fact for which the Dutch governments can be praised, has caused a disappearing of the great literary works. The main bulk of Dutch literature nowadays consists of little more than a combination of badly written pulp and unimaginative and even worse written true life tales not worthy to even be in the magazine racks next to the historical romance novels written for middle and over aged bored housewives.

The good and great contemporary literature of social thought, expression, reflection and critique of the Dutch is, today, sparse and far between.

In principle I have nothing against clear, enjoyable writing. In practice, it depends.

Some critics, readers, and unfortunately an increasing amount of writers and publishers claim the perfection a writer should strive for in his works is readability. This readability would then not only make him the most perfect novelist but also the most read. Or perhaps better put: the one who sells the most books. This, in its core, is where I believe the death of good literature will originate from. Sure, they are readable and enjoyable but can they thus be truly considered perfect novelists? Or are they just writers? Or just glorified, well paid, capitalistic story-tellers?

Now here is a question I would like someone to answer for me: Why do some of the best selling authors sell so much? Is it because their books are enjoyable and easy to follow? Is it because they tell stories that keep the reader in suspense?

I believe the answer to be no. They sell and they are so popular because their stories can be understood. That is, because the readers, who are never wrong – and I don’t mean as readers, obviously, but as consumers, of books in this case- understand their novels or stories perfectly.

It is, of course, only reasonable to accept and indeed to demand that a novel should be clear and entertaining, since the novel, as an art form, is at best tenuously related to the great forces that shape history and our private stories. Nevertheless, when the rule of clarity and entertainment-value is extended to serious literature the results can be catastrophic although the idea, the ideal, remains compelling, a goal to be desired and aspired to in the long run. But not a point of departure.

Books written with readability as their primary goal are often enjoyable to read, I can’t deny that. They aren’t short of clarity either. And the socially weak, the powerless or the less/non-educated can understand the message or the story perfectly. The average man and woman on the street can easily understand them.

Before I continue, I have to express that I have nothing against this simple literature per se. I am completely for any writer to remain free to make whatever declaration he or she wishes to proclaim in any way their taste is inclined. To be free to say and write what they want to write and publish it as well. I am against censorship and, to a large extent, self-censorship. But on one condition: if you are going to say what you want to say, you are going to hear what you don’t want to hear.

Now back to what I do consider to be the problems cause by the dominance of the bestseller in today’s bookstores, and more broadly speaking western society as a whole. The problem of this bestseller culture is the disappearance of the important author, the social critic, the observer and the commentator. Hardly anyone nowadays still reads Broges, Kafka, Camus, Satre, Thoreau or even Marai, Salinger and Kerouac if they are not forced to do so by their teachers or lecturers. Some names or works have already disappeared and many more will soon also be swallowed up by the mechanisms of oblivion. If you require proof of this, I dare you to find or order a copy of Satre’s The Die are Cast/ The Chips are Down. This has become the age if the writer as civil servant, the writer as thug, the writer as gym rat. There is an avalanche of glamour pouring into the literary world.

What do writers do to counter this insurgence of glamour? Not much. They can write. But writing and literature are worthless if they aren’t accompanied by something more imposing than mere survival. Literature nowadays means success, by which I mean social success: massive print runs; translations into more than thirty languages, several houses, dinners with the rich and famous, making the cover of magazines and landing huge advances.

Writers today are no longer young men unafraid to inveigh against the norms of respectable society, much less a bunch of misfits, but products of the middle classes determined to scale the Everest of respectability, hungry for respectability. They don’t reject respectability but desperately pursue it. They sign books, smile, travel, smile, make fools of themselves on celebrity talk shows, keep on smiling, never, never bite the hand that feeds them, participate in literary festivals and reply good-humoredly to the most moronic questions, smile in the most appalling situations, look intelligent and always say thank you. They flash their bleached white smiles as they prostitute themselves through the television screen. And why? Because they have to sell themselves before the buyers lose interest. It would seem Barthes was right (in more ways then one); ‘the author is dead’ or at the very least dying out…

Haruki Murakami’s ‘1q84’

After selling milions of copies Haruki Murakami’s latest novel is about to be released in selected European countries this summer. Its release in Japan caused for quite a stir, creating Harry Potteresque scenes in front of bookstores as its storyline was kept a secret until 00:00 of the day of its release.