Can You Hear Me?

The Importance of Voice in Identity and the Recognition of the Other.

In this article I will argue for the importance of Voice in our understanding of human identity and argue that the recognition of the Other is not dependent on vision alone but is supported by at least two of the other senses; touch and hearing.

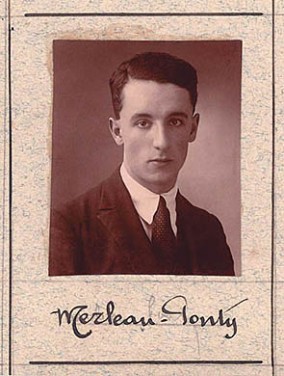

A child’s vision takes time to develop, a new born can only distinguish forms and object a couple of inches away, yet their hearing and sense of touch are often more, or even fully, developed at birth. Indeed a baby, before being able to recognize the Other visually and before they are aware of their bodily limits and image, Lacan’s ‘mirror stage’, they, through touch, are able to recognize the difference between touching and being touched, in other words, the physical limitation of their body. Or as Merleau-Ponty (1962) argues on the importance of the body; ‘the body catches itself from the outside engaged in a cognitive process […] and initiates ‘a kind of reflection’ which is sufficient to distinguish it from objects.’(107).

Furthermore, a young baby already possesses audio recognition and memory at birth. A statement reported by pre- and postnatal experiments with recorded music which showed recognition in their brain activity when playing back songs played to them while still in the womb. Moreover, a young baby is swiftly able to recognize the voices of its parents as distinct from their own, a process that happens faster than that of visual recognition, something that is supported by young children’s often misidentification of people, including their parents. Furthermore, recent research done by the German Dr. Kathleen Wermke into audio-recognition in infants and young children has shown that at the moment of birth they have already taken up their parents accent in their crying, a french baby’s cries have a different pitch and tone than that of say a german or japanese baby.

It could therefore be argued that audio recognition, and the recognition of the Other’s Voice is rooted more strongly and deeply in our conscious and unconscious memory. This idea finds it support in different fields of research. One angle of support can be found in a hole in Lacan’s theory of Self and the Other and his Mirror Stage.

The importance of the visual in Lacan’s Mirror Stage, in the shaping of identity and the concepts of the Other does not recognize the congenial blind. Lacan’s theory would imply that those born without sight would also be unable to form a sense of self and be unaware of the Other. This highly unlikely scenario does not appear to be the case as both young and mature blind people understand and are aware of the concept of the Other. Indeed as Jim Swan argues in Woodmansee & Jaszi (1994) book The Construction of Authorship blind people have a keen awareness of their identity and the Other and are in fact more reliant on the Other, on spoken language, discourse and memory for their understanding of the world as this is created through different forms of narrative. Through different forms of interaction with the Other, by asking someone to narrate the unfamiliar environment to them or with help from a seeing-eye dog, by relying on an extension of themselves in the form of a cane or stick or by remembering the familiar, the blind person’s brain narrates the world and the Other to them.(60-63) A fact that is reminiscent of Merleau-Ponty argument that we only see a segment of the world at a time and that we, through memory and expectations, fill in that which we cannot see but we know or believe there to be. In other words, our brain narrates the world to us.

Further support for the importance of Voice in our identification and recognition of the Other comes from a rare neurological disorder called Capgrass Syndrome. Capgrass Syndrome is a rare disorder that is related to Prosopagnosia in which those suffering from the disorder ‘come to regard close acquaintances […] as ‘imposters’, i.e. he may claim that the person in question ‘looks like’ or is even ‘identical to’ […] but really isn’t.’(Hirstein & Ramachandran, 1997:437) At times this can, in even rarer cases, be extended to misidentification of their own mirror image as not really being themselves.

Research by Hirstein and Ramachandran (1997) on this disorder has suggested that identification of the Other and the recognition of the Other is split into two; a conscious recognition and an unconscious recognition. Those suffering from this disorder misidentify people closest to them as looking identical to the person they remember but are in fact imposters as there is something not quite right. A feeling mirrored in C. L. Moore´s (1944) No Woman Born. Final support for the importance of Voice in our identification and recognition of the other is the fact that this misidentification of the other only occurs when confronted visually but does not occur when presented with the Voice. This is again something mirrored in No Woman Born in which Deidre is not really seen as Deidre until she has found her original voice again, ´the soft, husky, amused voice he remembered perfectly.´ (269)

Hayles, Katherine (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics, London: University of Chicago Press

Hirstein, William & Ramachandran, V. S. (1997) Capgras Syndrome: a novel probe for understanding the neural representation of the identity and familiarity of persons, Proceedings of the Royal Society 264, 437-444

Lyotard, Jean-Francois (1984) The Postmodern Condition: a report on knowledge, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Marcel (1962) Phenomenology of Perception, London: Routledge

Moore, C.L. (1944) No Woman Born

Leave a comment